Cardiology’s Emblem

Over the centuries, the red playing-card heart has become a symbol familiar to us through art, architecture, advertising and kitsch; it is cardiology’s emblem across the world.

The pre-Christian times

There is a bulbous, baked-clay goblet in the Museum of Kabul in Afghanistan which dates from the first half of the 3rd millenium B.C., depicting stylized fig leaves with broad stems. This decoration can be found on later ceramics of neighbouring cultures. As well as other vegetal decorations there appear these same fig leaves – and later ivy leaves – which anticipate the modern heart shape.

Approximately 1000 years later these botanic patterns appeared on Cretian clay vessels; fresco painters decorated scenes of figures in Minoan palaces with naturalistically painted tendrils of ivy, heart-shaped leaves and flowers.

paintings

(photo: A. Dietz)

The Acheans, heirs of the Minoan culture and bearers of the Mycean culture group, adopted the stylized ivy leaf in their ornamentations, and in the later 8th century B.C. Corinthian vase painters depicted these ornaments on cymations, the decorative borders of vase pictures and on the handles of vessels.

In many cases even grapes are portrayed heart-shaped.

This decoration is a foretaste of the metamorphosis into the heart, as it is described in Christian teachings, portraying Jesus as a vine with a divine, unselfish heart.

Heart-shaped ivy and vine tendrils can be found on vase paintings of Dionysos, the god of wine, frequently in erotic scenes.

On Grecian stelae and later on Roman gravestones and early Christian graves in catacombes, the ivy leaf symbolizes eternal love, i.e. love beyond the grave.

Metamorphosis from heart-shaped leaf to heart

The final transformation of the ivy leaf into the red playing-card heart of spiritual and physical love took place parallel to the secularization of the religious heart metaphor into the wordly, courtly heart found in the literature of the middle ages.

The monastic illustrators, inspired by art and ornamentation of the latter years of antiquity and Roman times, painted Trees of Life with heart-shaped leaves; in paintings of the 12th and 13th centuries, ivy leaves appeared in love scenes, before long in red – the colour of warm blood, which had signified good luck, health and love since prehistoric times.

From then on, the red heart spread quickly across Europe, especially in the area of the Catholic Church. Several facts are responsible for this:

- The profanation of the heart-shaped leaf to a symbol of physical love, but also to a symbol of compassion and devotion in secular and religious art.

- The adoption of the heart image in the Sacred Heart cult of the Catholic Church.

- The use of the symbol in heraldry, as a watermark in paper production, and as a company stamp in art printing, which was at the same time an anticipation of modern commercial art.

- The inclusion of the heart in the deck of cards: at the end of the 15th century cards began to be standardized, especially the symbols. The red heart replaced the goblets found on Italian tarot cards.

The close of the Middle Ages till the baroque period

Heart-shaped leaves and hearts can be found on gothic grave stones relatively often. They indicate the origins of families whose fiefs usually lay next to larger stretches of water or where rivers ran through.

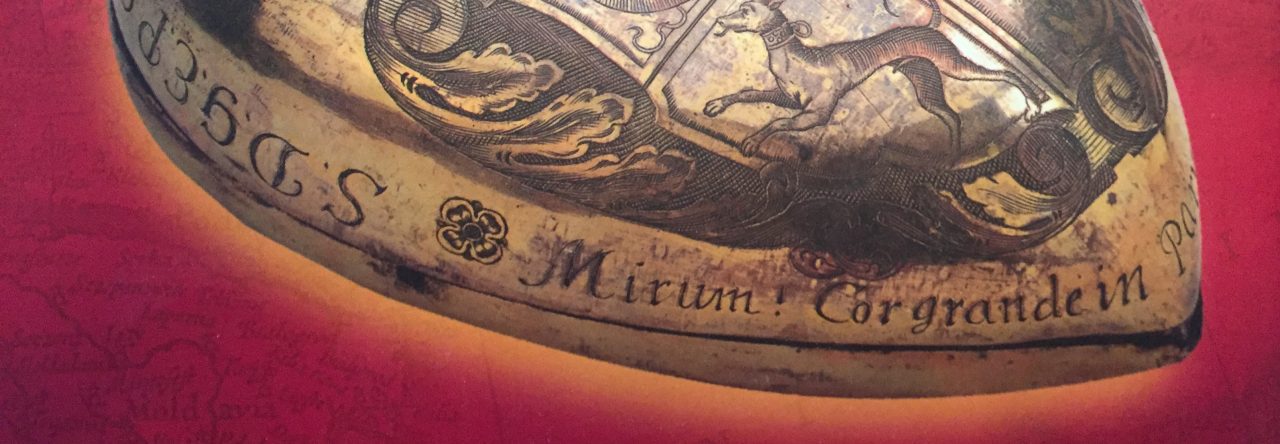

Later, in the Renaissance and especially in the baroque age, the heart on a coat of arms stood for eternal faithfulness and courage.

Painters and sculptors portrayed the human heart in the form of the playing-card heart more and more often, especially when they wanted to depict erotic and religious subjects.

European spiritual and secular sovereigns chose a separate grave for their heart in a place that they were fond of during their lives.

The urn was often heart-shaped, or the grave or cardiotaph was marked by the heart symbol.

The heart symbol in medical illustrations

The first medical illustrations of the heart were shaped like pine cones or pyramids, and were probably influenced by the description of the organ by the hippocratic school, by Galen and later by Arabian doctors. Later, from the 13th to the 16th centuries, the organ is depicted in the form derived from the ivy leaf.

The knowledge of anatomy which Hellenic physicians had gained through autopsies had sunk into oblivion during the Middle Ages, which were characterised by religion. The anatomists were inspired by artists and book illustrators, and portrayed the heart as an inverted leaf, with the tip bent to the left and the stem symbolizing the arterial tree.

Even the universal genius Leonardo da Vinci used this analogy between the leaf symbol and the realistic shape in his early anatomic sketches.

Perhaps the Norman stonemason, who made a porphyrite coffin for the Hohenstaufen emperor Heinrich VI, had the heart in mind when, following the Roman example, he created the mysterious leaf symbol with 4 grooves (= 4 ventricles?), the tip pointing to the left, and the stem (vessel stalk?).

If we compare this depiction with the early drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, then the picture becomes more and more fascinating.

The ring with the heart-shaped ivy leaf held by the divine hand, is an ornament symbolizing eternal love, a so-called “corona vitae” – the crown of life – a symbol of love beyond death, and was taken over from the ancient Roman world by Christian symbolism.

The expansion of the heart symbol across the world

Whilst, since Vesal at the latest, the heart is depicted in medical illustrations in its anatomical form, the red card-game heart, as symbol of spiritual and physical love, but also of lesser feelings, started its triumphal march from the european culture area across the whole world.

A decisive contribution to this was made by the Sacred-Heart cult as a religious sign which the Jesuits spread across the world.

In sacral art angels and saints hold their hearts in their hands like playing cards and give them to God as a sign of their self-sacrificing, everlasting love.

Interestingly, in Buddhism the playing-card heart also developed – independently of the western metamorphosis – from the fig tree (the bodhi tree) into the symbol not of love, but of enlightenment.

It was under such a tree that the ascetic Gautama found liberating enlightenment through years of meditation and became the Buddha.

Today, the symbol with the two curves, running down to a tip, is a pictogram for a whole range of feelings and has become the emblem of cardiology.

The prehistoric potters in Afghanistan and the greek vase painters did not associate the ivy leaf decoration with the heart of ancient times.

The vegetal symbol however absorbed so much meaning in the course of european cultural history that it turned into a general and exclusive, optically unique symbol of this central organ, and in human consciousness a hint of the ancient idea of the seat of the soul, of love and indeed of consciousness and thought, is still discernable.

Leave a Reply