Eternal Hearts—History of Heart Burial in Europe

Please note: This part of the website is still under construction!

Introduction

Heart burial, that is the interment of the heart separately from the body, is a ritual that was limited to the Christian West, i.e. Europe. From the beginning it was a ritual reserved through the centuries for the nation’s elite—the aristocracy and high clergy. In the cultural history of the heart it is this funerary custom which most impressively embodies the magic which this simple muscle performs on people—a muscle however with a fascinating physical performance.

Since the origins of man the heart has been the organ which represented human personality, life and vitality, both in the West and for many cultures beyond Europe.

It was the organ most prominently felt with emotion—its injury and demise meant death for man and beast. It was the seat of all good and bad qualities. This belief, both of the ancient Egyptians and of classical Greek philosophy, that the soul is to be found in the heart, was taken over first by the Jews and then by the early Christians. And so the history of the heart in Europe is also the history of the soul. Indeed, it became necessary for the church fathers to state in the council of Vienne 1311 that the soul is resident in every part of the body.

The belief in the immortality of the soul, grounded in Christianity, combined with the conviction that the soul resides in the body, i.e. the heart, was the essential root of heart burial.

Since primeval times the human heart has been an object of magic, mystic, cruelly-bizarre, pompous, melancholic, romantic, sentimental-kitschy and eccentric rituals. In poetry, love and life beyond death remain associated with the pounding human heart. In Goethe’s “Herz, mein Herz, was soll das geben, was bedränget dich so sehr”, it beats to the rhythm of Beethoven’s musical setting. Even medical progress, beginning with the discovery of the circulatory system by William Harvey in 1628, could not do much to change this. By describing the function of the heart, which even for him continued to be the powerful sun in the microcosmos of the human body, he did not demystify it at all.

The miraculous, restless spring in the clockwork mechanism of the human body – as the Cartesian physicians interpreted it regarding the divine engineer – contuinually confronts even today’s heart surgeons and cardiologists with new riddles. Their contribution to “heart burial” is to this day the most significant form of delaying death; by taking the live heart from a dead body and putting it into a living person, this person’s life can be prolonged for a further period of time.

Even the stone-age hunter interpreted the hammering in his chest, in the excitement of the fight, in joy and sorrow, as the sign of life as such; he knew that the pulsating red river of blood flowing out of the breast of his prey or his defeated opponent was evidence of death. For the inhabitants of Mesopotamia, the ancient Greeks, later the Etruscans and Romans, but especially for the ancient Egyptians, the heart was the central organ, it was considered to be the seat of the mind, the character and even the soul. This view was taken over by Judaism and early Christianity as a matter of course and it took a resolution of the Council of Vienne (1311) to clarify that the soul was resident not only in the heart but in the whole body. 40 years later, the mystic Conrad of Megenberg, in his “Book of Nature”, supported the compromise that the soul was hidden half in the heart, half in the brain.

body, an angel offers protection. Drawing in an Ars moriendi from

England, 14th century (Wikimedia Commons)

Until this day, the Western World has not been able to give up the conviction, just like the pharaos and their subjects, that the heart represents the human being as a whole. The literary critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki says that no other noun is used so often and in so many compounds as the word “heart”—at least by the Europeans.

Countless works of writers and poets are devoted to this topic, and no other non-geometric symbol, except perhaps for the cross, is used so much in art, architecture, graphics, advertising and decoration as the red heart symbol. The desire that, after death, the heart should be buried—and perhaps even live on—in a place that had a special meaning for the deceased or that he had been especially fond of, led to the curious practice of separate heart burial.

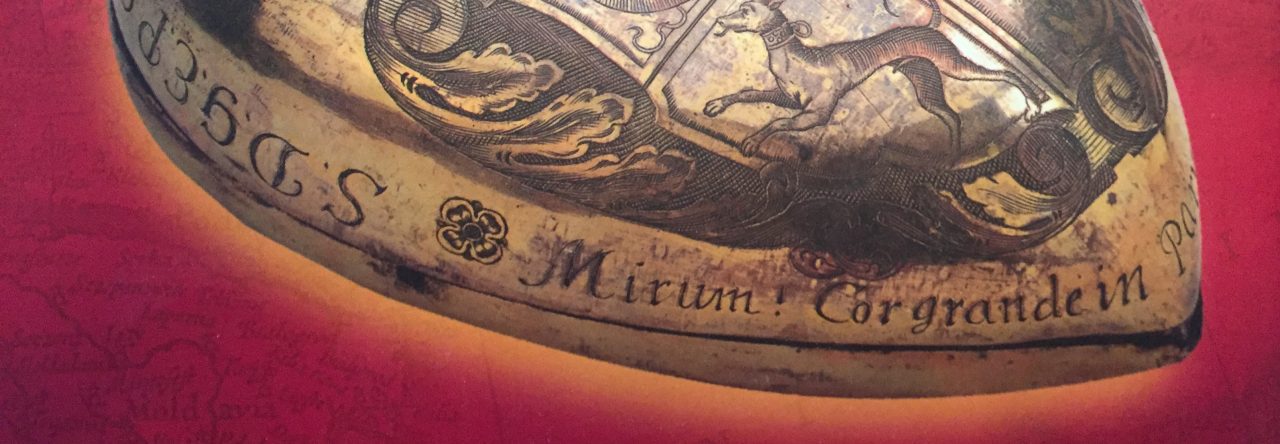

The earliest accounts of this funeral custom were a mixture of fact and fiction, the first evidence dates from the 11th century A.D. From then on it was above all the rich, the powerful and the high dignitaries of the church in Europe, and in the 19th and 20th centuries artists, writers, romantics and celebrities who provided for a separate burial of their heart. These included dynasties such as the Habsburgs of Austria, the Wittelsbacher of Bavaria, the Valois and Bourbons of France, as well as personalities such as Richard the Lionheart, the commander Tilly, Napoleon, Lord Byron, Chopin, Coubertin ( the founder of the modern Olympic Games) and finally the last Austrian Imperial couple Karl I., his spouse Zita of Bourbon-Parma an their first son—and formerly heir to the throne—Otto of Habsburg and his spouse Regina of Saxony-Meiningen. The custom embodies in an especially impressive way the particular fascination that the heart has exerted on mankind until the present day – this so uniquely perceptible organ, the death of which was in the past tantamount to physical death.

Leave a Reply